Jessica visited the exhibition “Monet and the Birth of Impressionism” at the Städel Museum in Frankfurt.

Once upon a time – and it was a time when my mind was as yet to be formed by art theories, art historical knowledge and such – I fell in love with Monet’s paintings. At this point of time, for me a painting was just a painting and I either liked it or not. Nowadays, it is not that simple anymore and over the years the way I look at art has changed.

Back then, my love for Monet was one that rose purely out of the beauty of his paintings. His art is indeed easy to love, maybe because it does not require explanation or certain knowledge to be understood. It can simply be enjoyed. And yet, with the awareness I have now, there comes a new fascination for Monet’s work. As per usual, there is always more than meets the eye. And beauty, after all, is just a surface.

There is a great exhibition currently running at the Städel Museum in Frankfurt that is dedicated to Monet and the birth of Impressionism. Over 100 paintings from Monet, Degas, Renoir, Sisley, Pissarro and Morisot give an overview of the formation and development of Impressionism. With an emphasis on Monet and his paintings, this stunning show traces the historical conditions that provided the setting for the origin of Impressionism and also tracks how it was perceived by the public. Monet’s work, so clearly opposing the then approved style of art, was considered not only to be daring, revolutionary, scandalous but also ugly. With his paintings, he struck a path towards a new art in the 19th century. He and his fellow Impressionists can indeed be regarded pioneers of modern art. Especially Monet’s late work clearly exemplifies this step towards modernism. But the new is often not appreciated at first, instead it is rejected. The first Impressionist exhibition (in 1874) was hence even described by one of the leading art critics of that time as “a museum of horrors”. Today, this attitude towards Impressionism has changed and the exhibition in Frankfurt has to be called a remarkable feast for the eyes.

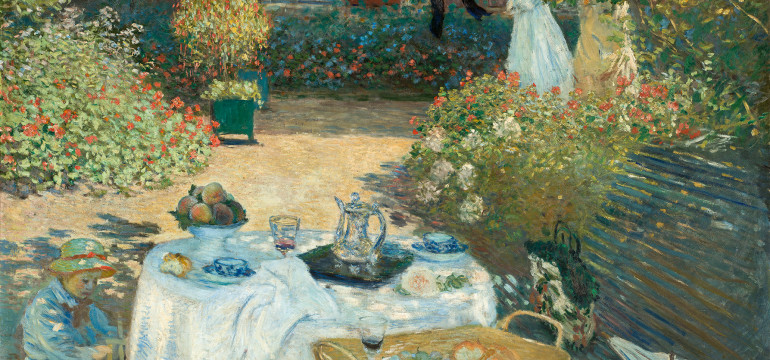

Claude Monet painted not only with brilliant colours but apparently with light itself, his brushwork is free and visible, not restricted but passionately unleashed. Monet was able to catch rays of sunlight and ban them on his canvas. He caught the wind in the fields, the smell of the flowers in his garden and the fleeting reflections of trees in the water of a pond. His landscape paintings appeal to all senses, showing nature as a sensual force. Thus, he created vibrant impressions that are full of atmosphere. But Monet also painted city life, boulevard scenes, architecture and people. He was an attentive observer of everyday life and considered nothing too small or too trivial to be painted. Monet therefore did not shy away from painting domestic life and immortalizing it on a huge canvas. “The Luncheon” from 1868 is the perfect example for this. It is one of the highlights of the Monet exhibition in Frankfurt but also one of the attractions of the permanent collection of the Städel Museum. This painting does not yet show the radiant colours of Monet’s later works, but instead rather low-key colours similar to those of the art works approved by the Salon. His subject, however, clearly sets itself apart from the themes depicted by Salon painters. Monet’s narrative picture captures ordinary family life. He recorded a scene during lunchtime, the table is set, and there are eggs and bread. His wife (who was not yet married to the painter at the time Monet painted “The Luncheon”) and little son are about to eat, the painter’s own place at the table is still empty, the newspaper unopened, ready at hand next to his plate. Apparently the painter was too busy to sit down because he wanted to record that one moment. Monet caught an impression of life that today would show up in pictures posted on Instagram or Facebook – a short moment in time considered to be worth sharing.

The exhibition at the Städel emphasizes that “The Luncheon” from 1868 is also a turning point in Monet’s work. From now on his palette became lighter, his brushstrokes increasingly cursory so that details were more and more eliminated. He painted more and more outside; his landscapes were not idealized settings anymore that conformed to an academic principle but they were reflections of what he saw – changes of weather and changes of light captured in paintings. Monet began to further develop his techniques and style which were then to characterize Impressionism. In 1873, Monet painted another “Luncheon” which is distinctively different from the older one. Here, the table is set outside in the garden, in the shadow of a tree. The flowers are brightly abloom, the women in the background wear white and yellow summer dresses, and a straw hat dangles from a branch. The air and atmosphere is light. This is the Monet I fell in love with. And after all I have learnt about art history, his art still touches me in a way that does not need explanation or reason. Isn’t this what art is about? Emotions and feelings? Or, as Monet himself declared: “Everyone discusses my art and pretends to understand, as if it were necessary to understand, when it is simply necessary to love.”

Claude Monet, Le déjeuner: panneau décoratif, 1873 – photo: bpk, RMN – Grand Palais, Patrice Schmidt © Musée d’Orsay, legs de Gustave Caillebotte, 1894

The paintings I have talked about and numerous more works by Monet and other great Impressionists can be seen at the “Monet and the Birth of Impressionism” exhibition at the Städel Museum, Schaumainkai 63, 60596 Frankfurt am Main. It runs from March, 11 to June, 21.

It is probably a good idea to get your ticket online: tickets.staedelmuseum.de

Jessica Koch

Featured image: Claude Monet, Le Déjeuner, 1873 (Detail), Photo: bpk, RMN – Grand Palais, Patrice Schmidt © Musée d’Orsay, legs de Gustave Caillebotte, 1894